A Joint Interview with Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni and Ian Merkel

Carolina Pulici and Jéssica Ronconi

Two recent books based on international archives draw on Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology of culture to deconstruct the mythical figure of the “uncreated creator” in order to reintroduce the social conditions related to the production and circulation of ideas and paintings. In Mulheres Modernistas. Estratégias de Consagração na Arte Brasileira [Modernist Women: Strategies of Consecration in Brazilian Art] published in Brazil in 2022, the Brazilian sociologist Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni examines the social and artistic trajectories of Regina Gomide Graz, Anita Malfatti and Tarsila do Amaral and specifically, their diver-gent access to international space, as well as the difficulties faced by Latin American artists in gaining recognition in 1920s Paris more generally. In Terms of Exchange. Brazilian Intellectuals and the French Social Sciences, published in 2022 in the United States and in 2024 in France and in Brazil, the American historian Ian Merkel takes a fresh look at French academic missions to Brazil in the 1930s, with the aim of demonstrating the weight of the South American country and of Brazilian intellectuals on the research and future careers of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Fernand Braudel, Pierre Monbeig and Roger Bastide. Given that both authors focus on the constraints of the international circulation of intellectual and artistic work, we deemed it fitting to conduct a joint interview with them via e-mail exchanges.

Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni is Professor of Sociology of Art at the University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil, since 2005. She has been a visiting professor at several foreign institutions, including the École Normale Supérieure (rue d’Ulm, Paris), where she also completed a postdoctoral fellowship between 2016 and 2017.

Ian Merkel is an Assistant Professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Groningen with tenure. He received his Ph.D. in cotutelle between New York University and the University of São Paulo and has taught at Cornell University, the University of Miami, the University of Turin, and Leipzig University.

Q: Your books are based on extensive research in archives in different countries. Could you tell us a bit about the development of these projects into monographs?

Ian Merkel (IM): During my doctorate, I became interested in Brazilian intellectual and cultural history. Initially, my plan was to write a history of São Paulo inspired by what Carl Schorske (1979) did many years ago for Vienna. I wanted to examine the effervescent cultural sphere of the city in the first half of the twentieth century in its various manifestations: artistic, social-scientific and political. It is through this that I came upon the “French missions” to Brazilian universities. Initially, these missions were only part of a broader project, but I quickly came to realize the potential for a monograph focused on them. Ultimately, it was the archives that informed my approach. Both Lévi-Strauss and Braudel’s archives had recently been made available in Paris, and the Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (IEB) at USP [Universidade de São Paulo] housed many papers from Monbeig and Bastide. Between these four thinkers, I had a significant basis from which to build outwards. I could reconstruct their experience and the Brazilian thinkers with whom they were in dialogue, including Mário de Andrade, Caio Prado Júnior, and Florestan Fernandes. [1].

Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni (APCS): My book was the outcome of many years of research dedicated to modernist women in Brazil. This research began in 2005 when I studied the trajectory of Regina Gomide Graz (1897-1973), who introduced modern textile arts (Art Deco) in Brazil. Despite her innovative approach, she remained largely obscured in Brazilian art history. Regina was married to the Swiss artist John Graz (1891-1980) and the sister of the Brazilian painter Antonio Gomide (1895-1967.) Together, they brought a modernist approach to decoration aligned with the principles of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total art, to Brazil. Regina’s name, however, was over-shadowed and subordinated compared to her male counterparts. Moreover, in dedicating herself to textiles, Gomide Graz renewed a traditional pattern in the gendered division of labor; she was less studied and exhibited than her husband and brother, and her work was less preserved.

In 2009, I joined the IEB at USP, an institution that houses important modernist archives fundamental to Brazil’s cultural history. At that point, I felt compelled to include more noteworthy examples, such as the artists Anita Malfatti and Tarsila do Amaral. Here, the challenges were different: it would be inaccurate to say that they were excluded, but it is also impossible to claim that gender played no role in shaping their careers and public recognition. Both are regarded in Brazil as prominent figures of national modernism, a role rarely attributed to women artists in a global context. How-ever, this recognition is not granted despite their gender; on the contrary. I point out that all three artists occupy narrative positions deeply shaped by notions of femininity: Tarsila do Amaral as the muse, Anita Malfatti as the victim, and Regina Gomide Graz as the collaborative wife. In that regard, Bourdieu’s thesis that the figure of the artist as a genius, and therefore individualized, is the product of a process within the artistic field itself contributes greatly to historicizing, and therefore denaturalizing, this vision. While Bourdieu provides the foundation for rethinking the creation of the singular artist as a myth, or collective illusion, when considering the myth of “female exceptionality” specifically, and particularly in the arts, I elected to draw on other references, such as Griselda Pollock, Tamar Garb, Christine Planté, Patricia Mayayo, and Séverine Sofio.

Q: Ian, in studying the importance of Brazil in France’s reshaping of the social sciences, you mention having drawn on Pierre Bourdieu’s lectures on the painter Édouard Manet to analyze Claude Lévi-Strauss’s “rebellion” against Émile Durkheim and the emergence of structuralism. Could you explain in further detail how Lévi-Strauss’s time in Brazil resonated in his thought, and how Bourdieu’s work informs your argument?

IM: It is a matter of the broader question of fields and how to understand the individual agents within them. Bourdieu recognized in Manet’s painting a kind of “symbolic revolution” that had trans-formed the world of art. Perhaps uncharacteristically of Bourdieu, he granted Manet a significant amount of autonomy in doing so. And yet, as he argued, Manet depended upon fellow painters, artists, and writers in homologous positions to enact the revolution for which he became so well-known. For Lévi-Strauss, I would argue that something similar occurred. He was inspired by Durkheimian social science but frustrated by its limitations. Ethnology (what we would now call Anthropology) provided a way out. Whether in 1930s São Paulo where he advocated for Cultural Anthropology instead of Sociology, or in 1950s Paris as the father of Structural Anthropology, Lévi-Strauss effectuated a kind of symbolic revolution. He was far from alone, however, in this task. We tend to think of structuralism as the fruit of Lévi-Strauss’s dialogues in New York with the linguist Roman Jakobson. But Brazilians such as Mário de Andrade, Heloisa Torres [2] and Luiz de Castro Faria [3] were invaluable collaborators on the ground. Lévi-Strauss’s French colleagues from Brazil, too, helped to bring both attention to and institutional support for his structuralist method.

Q: Ian, when dealing with the French missions to Brazil in the 1930s, you focus less on the contribution of these academic missions to the development of Brazilian social sciences and consider more thoroughly the impact of Brazil and Brazilian intellectuals on the work and future careers of French researchers in the beginning of their trajectory. Could you tell us more about this “effet de retour,” or in other words, how the Brazilian experience was reinvested in the French academic context?

IM: This question gets to the heart of what I ultimately argue in the book. I should recognize up front that the question of these “missions” has been one of serious scholarly research for some time now. Fernanda Arêas Peixoto’s work (1991), in particular, is pioneering in examining these French intellectuals in Brazil. But the archival sources made me profoundly aware of just how important this nucleus of Franco-Brazilian scholars in the 1930s was for the French social sciences after World War II.

Measuring influence is always a tricky thing to do in intellectual history. What I try to do in the book is to recontextualize “French” concepts such as structuralism and the longue durée in the transatlantic space in which Brazilians played a crucial role. As just one example, I highlight Caio Prado Júnior as a transformative influence on Braudel’s understanding of transatlantic trade and temporality. But there is also a broader institutional effect of the Brazilian missions on French intellectual life. The archives made it clear to me that the four French scholars who make up the heart of the book remained in close contact as they constructed their own social-scientific institutions in France. The École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, le Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale and the Institut des Hautes Études de l’Amérique Latine all bear the mark of the Brazilian years, not only because they hosted “Latin American” subjects, but also because they represented new kinds of empirical research.

Q: Ana Paula, concerning authors from peripheral nations who try their luck in central countries, Pascale Casanova (1999) argues that “if they wish to be noticed, they have to show that they are different from other writers – but not so different that they are thereby rendered invisible.” To what extent does this analysis shed light on the international circulation of the works of Regina Gomide Graz, Anita Malfatti, and Tarsila do Amaral? Is it relevant to say that the small percentage of these artists’ cultural production that achieved international recognition can be interpreted both as a form of exoticism and contingent on their exchange with the northern hemisphere?

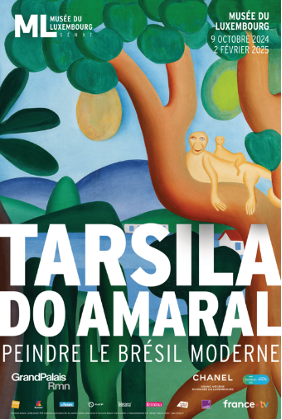

APCS: Traveling abroad was fundamental both for artistic training and for gaining recognition. In the nineteenth century, women were not allowed to enter art academies, neither in France nor in Brazil. Access to academic training was no longer the main issue for the modernist generation, but becoming a vanguard artist still required a period abroad. It was in Geneva that Regina Gomide Graz received the theoretical and practical training that enabled her to become a modern decorative artist; Anita Malfatti encountered artistic movements in Germany and the United States that allowed her to introduce modernism in Brazil in 1917. Interestingly, Tarsila do Amaral was in Paris between 1920 and 1921, but did not embrace modernism at that time. It was in São Paulo, after the Modern Art Week of 1922, that she better understood the debates among different artistic languages through her contact with the São Paulo modernists. During her subsequent stay in Paris, beginning in 1923, she took a “leap” into cubism, producing the most valued works of her career. Very few artists who did not study abroad managed to stand out; one rare exception is Mário de Andrade.

Q: Ian, you reject the thesis of the unidirectional transfer of ideas from privileged societies to those that are less privileged. How can we implement restrictions on the traditional approach to international borrowing without succumbing to relativism and cultural populism?

IM: Social theory is at a difficult crossroads. The main difficulty, in my view, is a global rightward turn combined with austerity that seeks to dismantle critical educational projects. There is also the broader question of how to remake curricula in the social sciences: for the most part, European and North American authors remain the classical, canonical references. They are “universal,” whereas thinkers from other parts of the world are valued primarily for their understanding of their local or national contexts.

In that sense, Bourdieu and Wacquant’s article (1998) is helpful for thinking critically about how authors and concepts circulate internationally. In the Netherlands, where I live and work, I try to use Latin American authors whose texts help to think beyond their local experience. Nowadays, U.S. based scholars are overrepresented in social scientific discourse. Remaining vigilant about why this is the case as we read them remains important.

Q: Ana Paula, in discussing the difficult recognition of Latin American artists in the Parisian art scene of the 1920s, you note that all those who achieved some measure of success took advantage of hailing from regions perceived as primitive and exotic. Could you tell us more about the expectations shaped by these artists’ national origins?

APCS: To “measure” success, I drew on the theory of circles of consecration from Alan Bowness (1989), Natalie Heinich (1998) and Nuria Peist (2005), which identifies exhibition in museums as the final stage in a cycle of accumulating recognition. Based on this, I investigated the entry of Latin American artworks into public collections in France between 1910 and 1947. In fact, very few Latin American artists succeeded in having their works acquired by museums: fewer than 10%. Among those, not all, but the vast majority in some way presented what France perceived as “typically Latin American:” representations of indigenous, multiracial, or Afro-Brazilian populations, “exotic” landscapes, and local customs (such as dances and folk festivals), for example. If we add to that the art criticism of the period and the vision of the École de Paris promoted by André Warnod, which claimed that the school included artists from around the world while expecting foreigners to contribute the “specificities” of their home countries, we begin to understand that there was a strong expectation of “otherness.” This often translated into a demand to perform a kind of exoticism, as Michele Greet (2018) has also analyzed.

Tarsila do Amaral was fully aware of this dynamic and stated it clearly in a letter to her parents, saying she “wanted to be the painter of her land” and that this tendency was well received in Paris, where the city was “tired of Parisian art.” In her chronicles, she also recalled that in her studio she organized lunches with traditional Brazilian food, cachaça, and tobacco to immerse the French modernists in a Brazilian aura of “exoticism,” which they greatly enjoyed. This is a clear example of how artists responded positively to the call to perform other-ness; it was valued in France, and it resonated well within the Brazilian art circuit. Anita Malfatti, who took a different path during her stay in France, did not receive as favorable a reception in France nor in Brazil.

Q: Ana Paula, the presence of Brazilians and even Latin Americans in global artistic and intellectual networks remains limited, which contradicts contemporary views of a current world of art and science that is truly more democratic. Do you plan to continue your research on which Mulheres Modernistas is based, and if so, how?

APCS: Currently, I am studying the presence of Latin American women artists in international rankings after completing research on Latin American artists in the Centre National des Arts Plastiques collection. This project has revealed something interesting: contrary to what the art world has disseminated, the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (1989, Centre Pompidou) did not have a significant impact on the inclusion of Latin American artists in French collections. This is important because the exhibition is seen as a turning point in global art history, in that it was to have promoted a greater inclusion of peripheral countries in the world of art. However, when I concretely studied the acquisitions, it became clear that they were much greater in the 1970s and 1980s due to the presence of many Latin Americans in France – expatriates due to the coups d’état that ravaged their countries – as well as the unique funding policy for the arts established by François Mitterrand. In the years following the famous exhibition acquisitions dropped significantly, and even during the apotheosis of acquisition and visibility of a “Latin American scene” in France gender inequalities were present.

Footnotes

[1] All three were influential Brazilian intellectuals: the literary critic Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) was a central figure in São Paulo’s early twentieth Century avant-garde movement; the economist Caio Prado Jr. (1907–1990) pioneered a Marxist and historiographic approach to understanding Brazil’s colonial society; Florestan Fernandes (1920–1995,) who succeeded Roger Bastide at the chair of sociology in the University of São Paulo, was a leading sociologist known for his studies on the indigenous society of the Tupinambá, on the integration of former black slaves in class society, and on Brazilian industrialization.

[2] Heloísa Alberto Torres (1895-1977) was a Brazilian anthropologist, one of the first women to join the National Museum of Brazil, where she later served as its director.

[3] Luiz de Castro Faria (1913-2004) was a founding member of the Brazilian Association of Anthropology and took part in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s expeditions in Brazil.

References

- Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1998) “Sur les ruses de la raison impérialiste”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 121-122, pp. 109-118.

- Bowness, A. (1989) The conditions of success. How the modern artist rises to fame. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Casanova, P. (1999) La République mondiale des lettres. Paris: Seuil.

- Cavalcanti Simioni, A.-P. (2024) “Des artistes latino-américains au Centre national des arts plastiques : les présences invisibles”, Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material, 32, pp. 1-34.

- Greet, M. (2018) Transtlantic Encounters: Latin American Artists in Paris Between the Wars. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Heinich, N. (1998) Le triple jeu de l’art contemporain. Paris: Minuit.

- Peixoto, F. (1991) Estrangeiros no Brasil. A missão francesa na USP. Thesis in Anthropology. IFCH-Unicamp: Brazil.

- Rojzman, N. (2005) El proceso de consagración en el arte moderno: trayectorias artísticas y círculos de reconocimiento. Matèria: Barcelona.

- Schorske, C. (1980) Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.