A Journal in the Service of Collective Sociological Practice

Franz Schultheis, Charlotte Hüser & Lilli Kim Schreiber

A Blind Spot in Transnational Reception

To this day, the modern social sciences remain constrained by the boundaries of their national affiliation and the historical structures of their respective emergences, although they incessantly emphasize the universal validity of their theoretical and methodological perspectives. As Pierre Bourdieu repeatedly pointed out, they are contemporary without really being so. It often takes decades for works or institutions that are of crucial importance to some to be noticed by others. Texts circulate constantly in the context of international exchange, often detached from their original context, and their reception isolates them from their original frame of reference.

Figure 1: Cover of an ARSS issue entitled “The institution of the school”. A journal beyond all academic conventions in terms of production form, format, layout, visuality, style, theoretical coherence, methodological stringency and empirical diversity.

The reception of Bourdieu outside France is a vivid example of this: although he is known worldwide as an outstanding author, the collective aspect of his work is often overlooked. This is particularly true of the journal Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales (ARSS). Franz Schultheis’ team, located at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen, Germany, recently published an article about ARSS in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) – one of Germany’s largest national daily newspapers with around 850,000 readers. The article entitled “Die Wörter und die Bilder” (“The Words and the Images”) drew on ongoing collective research. It introduced Bourdieu’s unconventional publication project, shed light on both visual sociology but also the special features of the journal and its extraordinary team of authors, and aimed to bring the German audience closer to a medium that is so far hardly known east of the Rhine. A look at the journal ARSS, founded by Bourdieu exactly 50 years ago, in 1975, demonstrates its significance for science communication and its influence on Bourdieusian research on the way to a trans-European sociological paradigm. This text is an updated version of the FAZ article.

From the very beginning, Bourdieu and his research team shaped the journal’s unmistakable profile. In particular, the dialogue between text and image became influential – a connection that already played a central role in Bourdieu’s early research in and on Algeria – which continued in ARSS. However, this particular practice of science communication, which began in 1975 with a kind of “undisciplined research,” remained anchored to Bourdieu’s strong authority – more in the sense of a Warholian “Factory” than a truly democratic research workshop.

This shows the necessary distinction between the “collective intellectual” – a theoretical counterpart to the “total intellectual” à la Sartre or Heidegger – and what could be described as the “Bourdieu collective,” i.e. the concrete team of researchers who played a decisive role in the emergence of ARSS. Bourdieu’s practice in this collective made the figure of the collective intellectual conceivable in the first place, even if it often remains invisible in the reception of his writings. Although he always worked closely with others, his work was usually reduced to the signature of a singular intellectual – especially in Germany, where, as Bourdieu himself pointed out, his texts are often read detached from the context in which they were written.

The Bourdieu collective, which is now considered emblematic of ARSS, is particularly evident in the style and composition of the individual issues. Not only were unusual topics such as fashion (ARSS Vol. 1, n° 1, 1975), holidays in the peasant environment (ARSS Vol. 1, n° 2, 1975), class-specific practices of marriage (ARSS Vol. 2, n° 4, 1976), or physical practices in Bali (ARSS Vol. 14, 1977) published. Equally decisive was the working method of the journal itself: instead of anonymous peer review and classic editorial structures, ARSS relied on a close exchange between an editorial staff and authors who understood science as a thoroughly collective process. Texts were not only edited but often developed together as part of ongoing research projects.

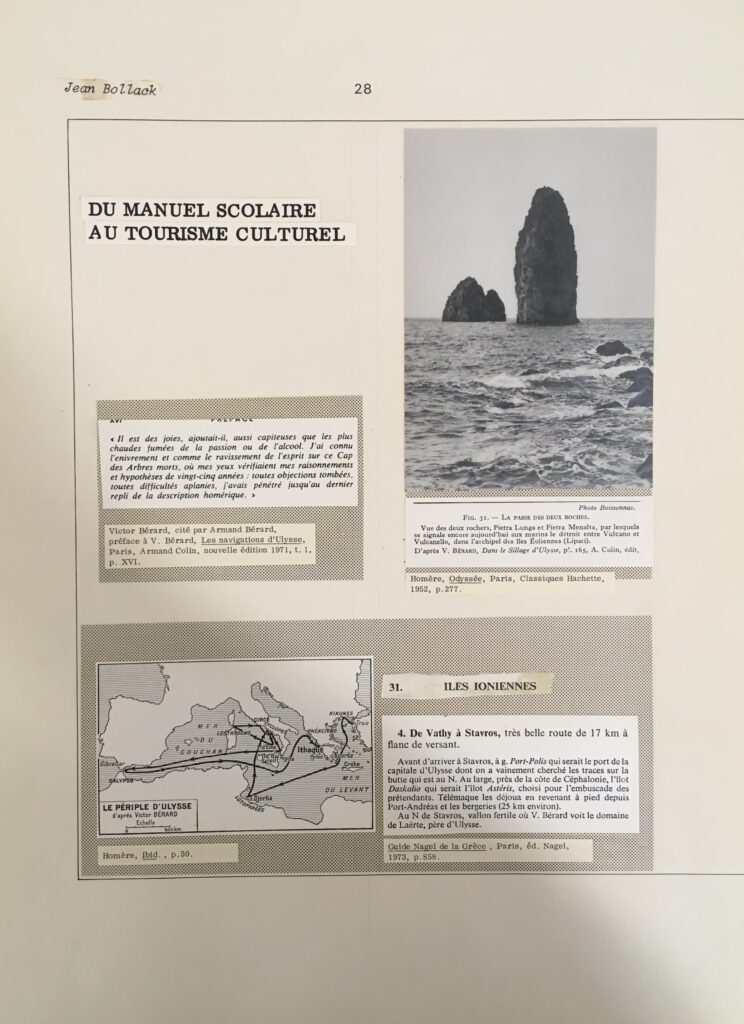

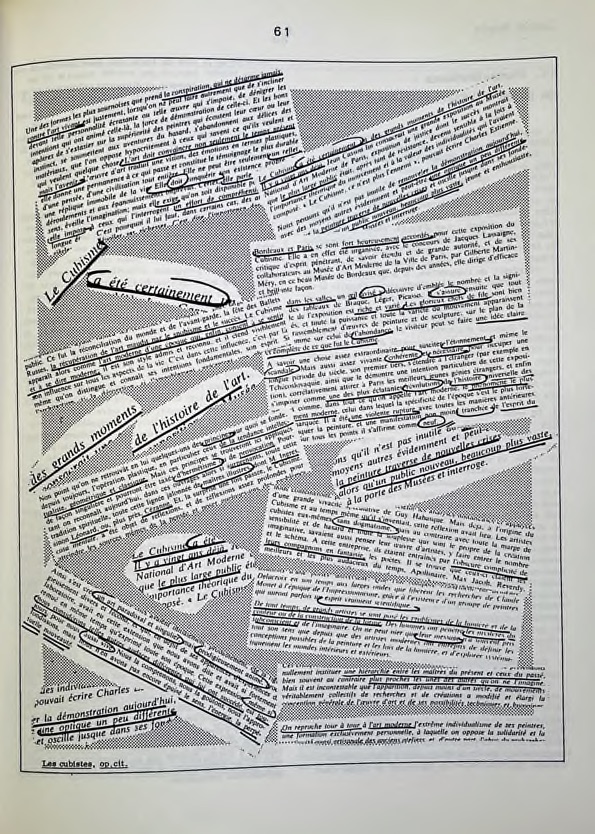

To counteract the ritual formalism of academic journals, which typically standardize research findings, ARSS relied on visual overload and the manual assemblage of newspaper clippings, underlining, and encirclements. This compositional principle shaped the early editions in particular, which were still elaborately handcrafted with scissors and glue.

Figure 2: Photographs and other visual documents create a dense representation of research practice and make the working process comprehensible. (ARSS Vol. 1, n°5-6, 1975, p. 28)

This production method required a collective that put together the individual booklets and took countless hours of work – an effort that seems dizzying today. The dense interweaving of image and text aimed to awaken critical reflexivity and participatory research by combining the visual with the conceptual. Through this material visuality, sociology itself could be experienced as a “material practice.” In the early years, photo editing was therefore a central part of this approach and itself emerged from collective work.

In addition, there was no editorial committee or scientific advisory board until the mid-1980s. The numerous authors who have contributed to ARSS over the years have been deliberately listed without academic titles or institutional affiliation. Bourdieu himself supervised all 140 issues – no contribution was published without his explicit approval.

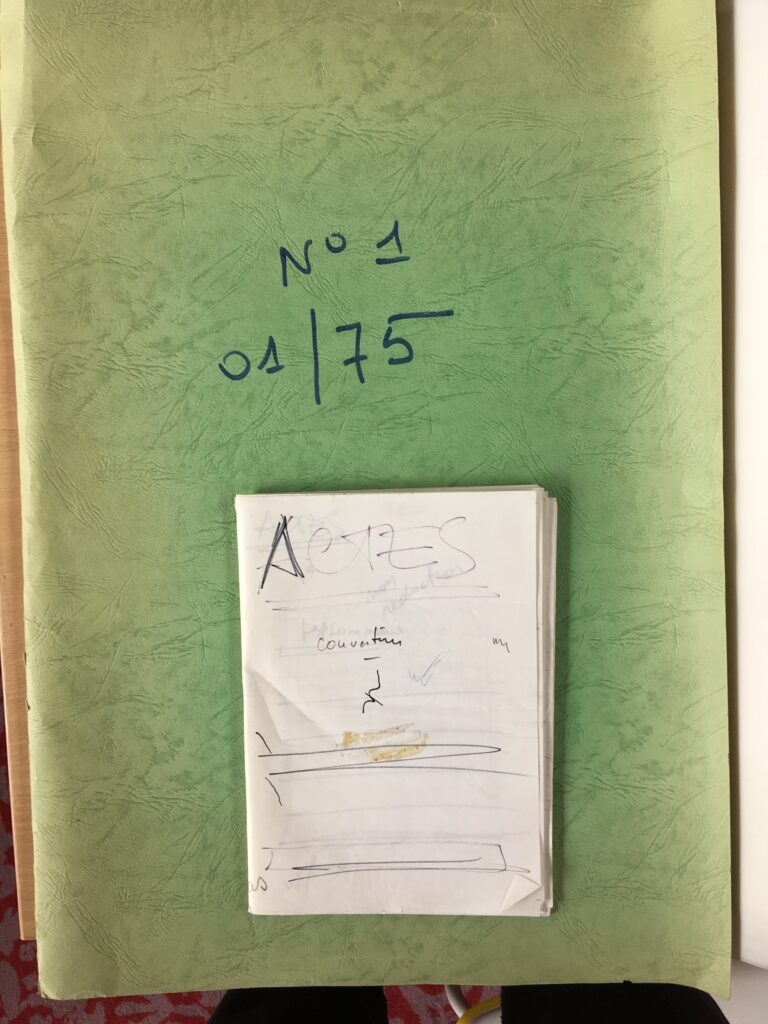

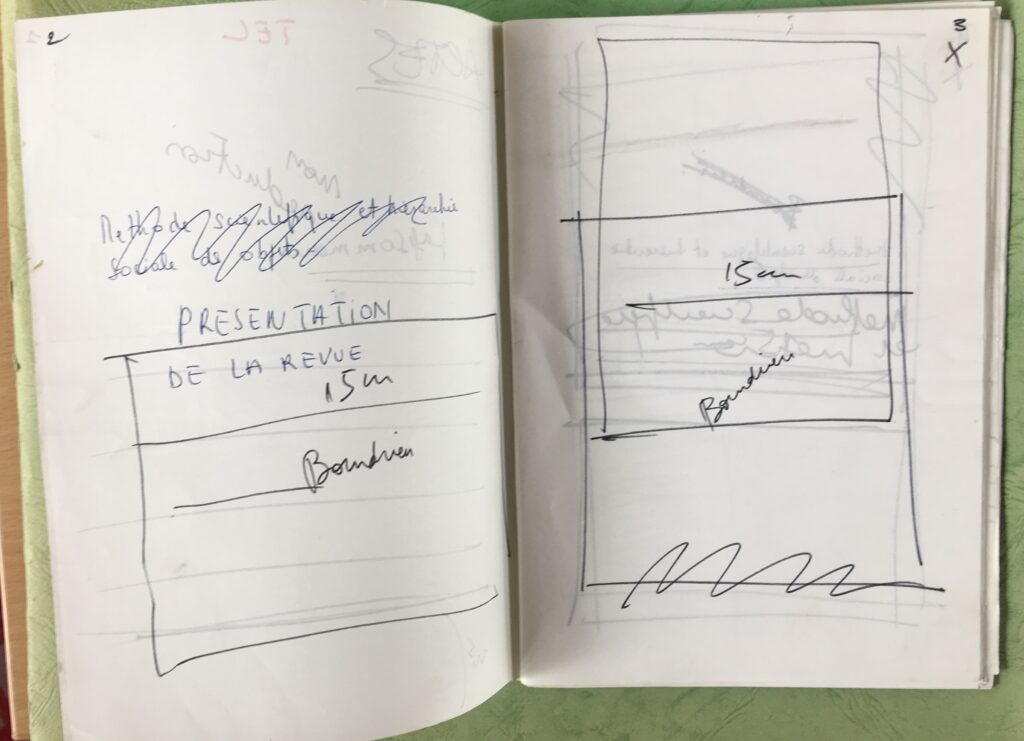

Figure 3: In the early years, Bourdieu took over the setting of the revue himself. For each individual issue, he drafted a detailed plan in which he determined the composition of text and image.

Conceptualizing the Visual, Visualizing the Conceptual

In its graphic and visual design, ARSS also broke with the academic conventions of contemporary journals, which pursued a conservative state of the art and, on top of that, largely presented only textual elements.

The print templates of text and images were composed anew for each issue to form a coherent whole. This creative process conveyed sociological ideas visually, and was more than a purely aesthetic packaging or a technical necessity. Jean-Pierre Jauneau, who worked as ARSS’s typesetter for many years, described how the journal’s character was also reflected in the typographic design of the titles, creating a visual syntax.

A central focus was on the visual elements: in addition to classic graphics and documentary photographs, there were also press photos, text excerpts from magazines, interview excerpts, handwritten sketches, illustrations, comics, personal drawings, caricatures, maps of cities and countries as well as ornamental graphics, emblems and copies from non-scientific magazines such as fashion magazines.

These were used partly for purely aesthetic reasons, partly in close connection with the text to support the argumentation. Particularly revealing is the question of the extent to which individual elements were aesthetically motivated, appear to be justified in terms of content, and to what extent they are largely independent of the narrative text as a textual element in the so-called encadrés – framed insertions that function as so-called paratexts (Genette, 1992) – and are intended to specifically encourage readers to think or conduct their own research.

The typical encadrés often emphasize central arguments and are reminiscent of infoboxes in newspapers. This innovative approach to visual and textual elements illustrates sociology as a constructivist and experimental practice. The layout was understood as a “composition” in which nothing was left to chance: each page was intensively discussed in order to achieve an optimal interaction between the different information carriers.

Figure 4: The collage technique serves to visualize a field of discourse – in this case, the art world and its tendency to verbalize art, accompanied by a cacophony of labels and underlinings. (ARSS Vol. 1, n°5-6, 1975, p. 61)

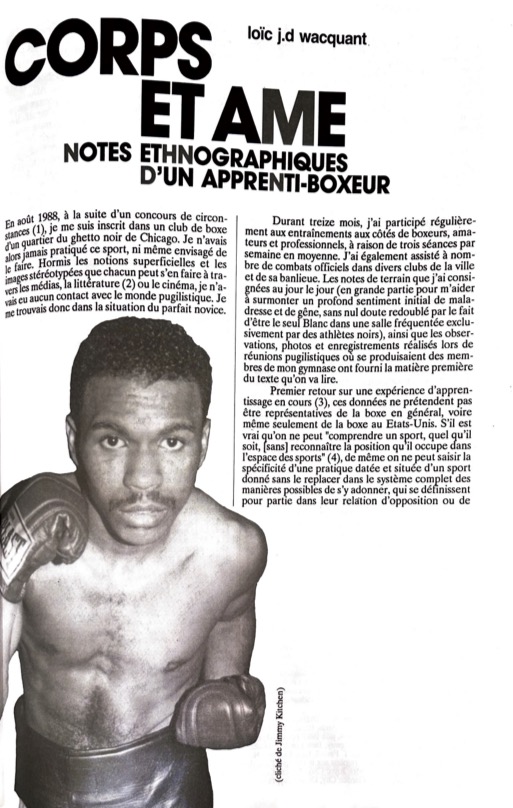

An emblematic example of this compositional style of ARSS is the text “Corps et âme” by Loïc Wacquant (ARSS n° 80, 1989). The chosen combination of the title “Body and soul” with the martial image of a boxer seems intriguing at first glance – and is supposed to. The long-time typesetter of the revue himself describes how the image, which immediately and aggressively catches the reader’s eye, in combination with the equally imposing title, offers an initial orientation (Duplan, Jauneau and Jauneau 2008, p. 39). This image-text dyad, supplemented by a more precise subtitle, guides the reader’s eye and makes it easier to classify. The experimental arrangement of text and image was not only an aesthetic decision, but also a strategic means of making scientific concepts and sociological theories accessible to a wider audience. The image acts as an eye-catcher, spontaneously arouses critical-reflexive curiosity and draws the reader directly into the article. The young Bourdieu had already experimented with these techniques of image-text montage during his ethnological-sociological field research in Algeria; for example when it came to recognizing gender differences in the daily work of the Kabyles or to show the reader the hexis – i.e. posture and gait – of the Kabyle “man of honor” based on the dense descriptions of his observations in a way that could be directly experienced by the senses.

Figure 5: Idiosyncratic title-text-image compositions, in which the object catches the reader’s eye, reflect Bourdieu’s claim to illustrate central scientific concepts – such as “habitus”. (ARSS Vol. 80, 1989, p. 33)

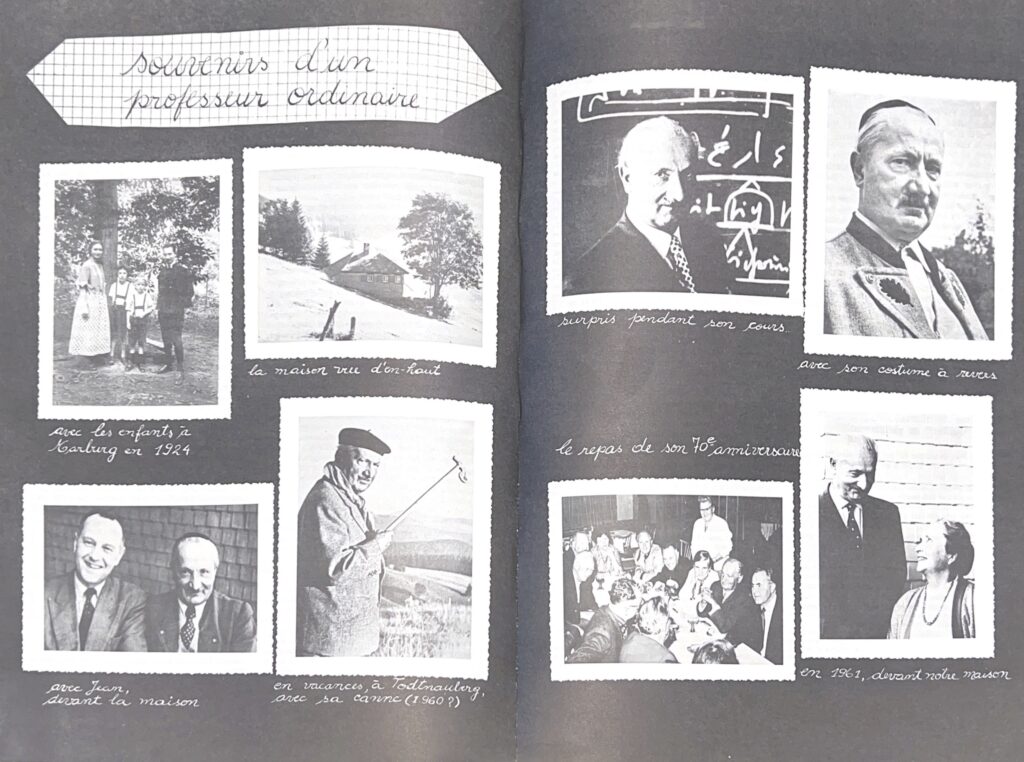

Bourdieu’s 1975 article “L’ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger” (Vol. 1, n°5-6, 1975) seems to be particularly typical of the provocative attitude of ARSS. It is a critical examination of Heidegger’s affinities with the Nazi regime, which until then had remained hidden behind the powerful Heidegger cult. A few years later, Bourdieu published a revised and more detailed version of the same article, retaining the original title, in the series Le sens commun (Éditions de Minuit, 1988), and in the same year it appeared in German as Die politische Ontologie Martin Heideggers (Suhrkamp, 1988). This is one of many examples of how ARSS articles served as a template for later publications. The article further shows that ARSS was characterized not only by its unusual form, but also by the deliberate use of “objective irony”: images that spoke for themselves in such a way that they needed no explanation. In his book Rendre la réalité inacceptable (2008), Luc Boltanski recalls a double page in the Heidegger article entitled “Memories of an ordinary professor,” “which we had a lot of fun with.” (Boltanski, 2008, p. 32) The editorial team collected private Heidegger photos – such as him in the family circle or in Swabian costume – and provided them with deliberately ironic captions. “We had put them together according to the model of the family albums that my brother Christian Boltanski used in his artistic work and thus turned them into works of art.” (ibid., p. 33)

Figure 6: In ARSS image montage is more than an illustration: the double page ironized Heidegger’s self-staging as a German professor and exposed his ideological positioning. (ARSS Vol. 1, n°5-6, 1975, p. 148f.)

Conclusion

The design of the early editions, which is deliberately reminiscent of bricolage (DIY), evokes an approach to the sociological collective “workshop” and suggests that the intention behind it was not to prescribe rigid rules such as a consistent rhetorical structure or a uniform article length. The central point here is not so much deductive reasoning as the demonstration of practice – a montrer et ne pas démontrer (to show and not to demonstrate). The text and image design of ARSS itself thus becomes evidence of the creative, and reflexive work of the research collective.

The multitude of research steps and text drafts were not created in mechanical routine, but rather in an organic, cooperative form – as a kind of atelier de recherche (research workshop). In this structure, collectivity and group cohesion play a central role, while at the same time mechanisms of the singularization of a collective author, Bourdieu, take effect. Throughout his life, Bourdieu pursued the concrete utopia (Ernst Bloch) of a “research collective,” as embodied for him by the encyclopaedists of the 18th century, in which the fruits of scientific work are not attributed to an individual, but to the collective. ARSS tried to put this vision into practice through continuous teamwork. The collectively shared, scientifically institutionalized habitus resulting from the practice of ARSS went beyond aesthetic commonalities as well as common content interests, and found expression in the perception of the journal as the mouthpiece of a kind of “Bourdieu school,” which was emphasized by the ironic label “les bourdivins” (based on Bourdieu and the so called divines) for the group around Bourdieu.

ARSS quickly developed into an autonomous “means of production” of scientific work and contributed to the institutionalization of a coherent scientific community, which over the years evolved into a paradigmatic entity that continues to shape Bourdieusian research both in France and internationally.

Whether the collectively shared but shifting constellations surrounding the work on ARSS, particularly between 1975 and 1985, actually justify speaking of a “Bourdieu School” (by analogy to the Durkheim School) is less important today than the scholarly fruits of this radically anti-academic endeavor. Further research could instead focus on the working methods of various chairs, research groups, think tanks, and international networks oriented towards Bourdieu’s work. A transnational comparative study of the continuation and dissemination of the forms of collective research and collective intellectual engagement initiated by Bourdieu could provide important insights in the future.

References

- Boltanski, L. (2008) Rendre la réalité inacceptable. À propos de “La production de l’idéologie dominante”. Paris: Demopolis.

- Duplan, P., Jauneau, R., Jauneau, J.-P. (2008) Maquette & mise en page. Typographie, conception graphique, couleurs et communication, mise en page numérique. Paris: Électre.

- Genette, G. (1992) Paratexte. Das Buch vom Beiwerk des Buches. Frankfurt/New York: Campus.