Julien Duval

The work briefly presented in this text draws from a previous research project on cinema. One of its aims was to explore the possibility of analyzing cinema in terms of field studies. There is some debate as to whether the cinema sector, where the costs of producing and distributing works are particularly high, has the same structure as the literary field analyzed in Les Règles de l’art (Bourdieu, 1996). While some sociologists recognize the opposition between mainstream and independent cinema, or between arthouse films (cinéma d’auteur) and genre films (cinéma de genre), as a clear manifestation of the opposition between the subfield of large scale production and the subfield of restricted production, others argue that figures such as Hitchcock and Spielberg demonstrate just as clearly that cinema is a field where it is possible to combine the successes of both a wide audience and recognition from specialized critics.

A more systematic approach in exploring this matter is to attempt to construct the field statistically, using the multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) technique that Bourdieu often employed for this purpose, followed by other researchers (Duval, 2018). This technique has the advantage of avoiding hasty comparisons. The analysis was carried out at a national level and focuses on France. I had considered a study on the international level, but constructing a database at this level seemed much more complex. This statistical difficulty may reflect the importance that the national scale has maintained, at least in France, in structuring a social activity such as cinema. Given that films are “talking pictures,” their circulation is affected by linguistic borders, as dubbing or sub-titling is costly, and not accepted by all audiences. Moreover, French cinema is organized in great part according to national sources of funding and award systems. Most French films are not released outside of France.

Statistical analysis led to the conclusion that the “cinematographic field” in France in the 2000s had, mutatis mutandis, a very similar structure to that highlighted in studies on the French literary field in the second half of the nineteenth century. However, “closed economy” reasoning is only ever provisional. The field of cinema in France cannot, in any lasting way, be considered as a perfectly closed microcosm, or as a self-sufficient set of connections. In order to fully grasp what is taking place in this field, we must at some point envision its participation in a larger space. For example, French films, and particularly those aimed at a wider audience, face competition from American films (in France, about half of all box office receipts are from American films). Some of them are also imitations or parodies of American films, which is a sign of dependence. Similarly, while France, like other countries, has its own national awards and equivalent of the Oscars (les Césars), recognition by international institutions, such as film festivals, also has a major impact on the national cinematographic scene. Is it possible to study cinema without considering the existence of a “transnational culture” related to cinema? While there is, to varying degrees according to the country in question, a “national culture” that rarely, if ever, crosses borders certain films, genres, and film celebrities do travel abroad, and others (sometimes the same) are known for having contributed to a history of cinema that is occasionally presented as “global.”

The transnational circulation of films and the (false) evidence of the notion of “world cinema”

It is thus possible to imagine a “transnational cinema space” (which coexists with national spaces, relatively autonomous by comparison) drawing from the model of the “world republic of letters” – of which a transnational cinema space could, in part, be a byproduct, as Pascale Casanova suggests. Furthermore, it is possible to gather elements to better define or characterize this space. For example, UNESCO collects national statistical data. This data is compiled according to procedures that undoubtedly vary somewhat from country to country, and can therefore only be compared with caution, though what the data does indicate is quite striking. The data reveals massive phenomena, such as the unique position of the United States, in light of many statistical indicators, or the existence of a group of countries that are major film producers (the United States, Nigeria, China…). However, is it possible to transcend these scattered elements and use MCA at a transnational level?

The obstacles appear to be numerous. As Yves Dezalay suggests (Dezalay, 2015, pp. 23-24 and p. 26), transnational spaces may be structures that are too complex to be analyzed with MCA. They may also be less institutionalized than national spaces, and therefore more difficult to grasp objectively. The fact that statistics may still be associated with States (thinking in etymological terms) presents yet another difficulty, in that a transnational society is a stateless society.

Despite these challenges, I have endeavored to statistically construct a transnational cinema space. The most satisfactory attempt is based on a set of national box-office figures. These figures reflect information that is relatively accessible in the field of cinema, within which economic recognition is perhaps more significant than in more culturally legitimate fields. The set is not exhaustive but comprises of 65 countries that have a certain amount of influence in the world of film. Therefore, the analysis focuses on a relatively homogeneous subspace (countries with a minimum number of cinemas and a system for recording box-office receipts), which is perhaps just as, if not more relevant to an analysis related to field studies. Box-office data made it possible (though not without material difficulty) to construct a series of indicators. For each film, I was able to calculate the total revenue generated in the various markets where it had been released and study the structure of this total according to the various countries. I then looked at other, “international” institutions. In cinema, as in other fields, there are no Nobel prizes or truly “international” magazines, but festivals that are viewed as “international” play a notable role. At the very least, these festivals are international in the sense that they present films from different countries to juries composed of citizens of different nationalities.

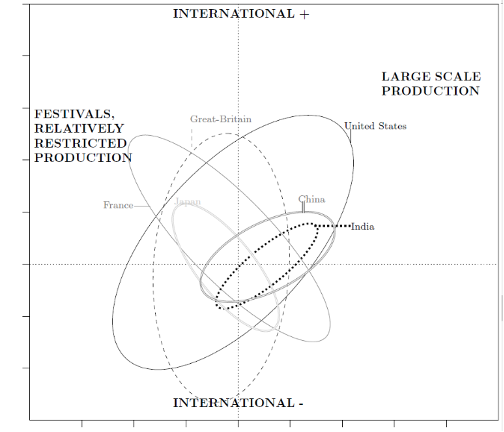

Statistical analysis of this data supports Pascale Casanova’s hypothesis that a correlation exists among transnational and national spaces, or the French space, in any case (1999, pp. 120-121). Within the transnational space, films are distinguished first and foremost by the degree to which they circulate outside their country of origin. A long continuum distinguishes the small number of films that circulate very widely around the world (or in the “world-economy” studied here) from a number of films that, without being totally confined to their country of origin, circulate very little outside of it. A second opposition identifies the “dualistic structure” of cultural production fields. Among the most “transnational” films, there is a difference between those that are exhibited in many countries and generate very high box-office receipts, and those that are distinguished not by their record box-office receipts, but rather by the fact that they are presented at the most prestigious festivals (Berlin, Cannes, Toronto, Venice…). The former corresponds to a production that is more widely distributed than the latter (which, incidentally, are shown in a slightly smaller number of countries). This dualist structure also refers to two forms of internationalization: internationalization produced by “market” forces alone, and internationalization associated with festivals. Effectively, many festivals present themselves as an alternative to the market. Statistical analysis confirms that the highest-grossing films are not those selected for festivals, but it also shows that a continuum links the two. Halfway between these two poles are films that have a certain amount of legitimacy, while still reaching a relatively large audience, and characteristics that are well-suited to an event such as the American Oscars.

A distinctive feature of this transnational space is that the films that circulate within it all have privileged ties to the national space (or even two or three national spaces) in which they were produced. Indeed, there is no such thing as a “transnational” or stateless film. Statistical analysis confirms that the probability for a film to circulate in the transnational space, and in any of its regions, is not at all independent of its national origin. For example, films that circulate the most on mainstream markets are nearly all American productions or co-productions. By contrast, Indian and Chinese films tend to occupy non-dominant positions in the large-production subspace: they can be extremely successful, but on a more regional scale. European films (like those from many “small” cinematographic nations) that circulate at all, almost always do so via festivals.

An initial and brief way of describing national power relationships in this transnational space is to emphasize the exceedingly unique position of the United States to then specify that few countries are able to even remotely compete with this position. China and India constitute a first form of competition: both countries boast a very large and protected domestic market – through political measures or consumer habits – and are not without significance in the wider production subspace. France, with its fairly strong position in the restricted production pole, represents another form of competition. Other countries (the UK, Japan, other Western European countries, Russia, South Korea, etc.) carry some weight in the space, but their position can likely still be characterized as being closer to that of France, or closer to that embodied by China and India.

Another way to briefly describe the balance of power would be to say that while the U.S. clearly dominates the space, it is in a central (and almost monopolistic) position in the wide release market, whereas the pole of restricted production is more polycentric. Our database (which underestimates the weight of U.S. co-productions) suggests that U.S. films account for at least two-thirds of total box-office receipts (and ten times more receipts outside of their own market than China, which comes second in this respect). By contrast, the U.S. accounts for only one-sixth of selections at major international festivals, where they face a more pronounced competition from France (one-tenth of selections), Germany, Japan, Italy… The representation of film exchanges organized around a center exporting to peripheries that trade little with each other therefore applies primarily to the mass market. At the pole of restricted production, Western domination can still be observed, though the centers are more numerous and, another difference, these centers are both exporters and importers.

A “planetary film” from 2024: Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3

Efforts to statistically construct transnational spaces related to cinema therefore seem worthwhile. However, two further remarks must be mentioned. First, Bourdieu’s observation that statistics are the result of an official vision (and have to do with the State at the national level) remains true at the transnational level: the data that can be used to construct space is associated with cinema attendance and ignores domestic consumption, which is sometimes similar to that related to cinema attendance, but not always. Specifically, statistics fail to consider transnational circulation – better grasped through anthropological approaches – which, like the abundant production from the Nigerian industry since the 1990s, takes place almost exclusively outside cinema networks (and on the fringes of central countries). Second, one cannot work statistically on transnational space without questioning the type of space it can form and how it relates to national spaces. Transnational space is undoubtedly homologous to national spaces, but not all national spaces are alike, and the balance of power within transnational space undeniably stem from the differences that exist among national spaces. Transnational space, as described here, is a kind of intersection of national spaces. Synthetizing this work, as I have done here, has the disadvantage of implying that a transnational space could somehow preexist national power relations, whereas it is more likely to be the product of these dynamics. The difficulties involved in constructing a transnational space should therefore not obscure the fact that, ideally, the construction of this space and the study of the relationships it maintains with national spaces is a simultaneous endeavor.

For developments on the points discussed in this article, see:

In French:

- (2020) “Une république mondiale du film”, COnTEXTES. Revue de sociologie de la littérature [Online], 28.

- (2023) “Les échanges transnationaux de films. De l’opposition centre-périphérie à la construction d’un champ”, Revue française de sociologie, 64 (4), pp. 659-689.

- (2024) “Le cinéma français et le monde. Note sur les relations entre un champ transnational et les champs nationaux”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, 253-254, pp. 68-83.

In Portuguese:

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1996) The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Casanova, P. (1999) La République mondiale des lettres. Paris: Seuil.

- Dezalay, Y., Bigo, D. and Cohen, A. (2015) « Enquêter sur l’internationalisation des noblesses d’État. Retour réflexif sur des stratégies de double jeu », Cultures & Conflits, 98, pp. 15-52

- Duval, J. (2018) “Correspondence Analysis and Bourdieu’s Approach to Statistics: Using Correspondence Analysis Within Field Theory” in Medvetz and Sallaz. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Pierre Bourdieu. Oxford : Oxford University Press, pp. 512-527.