Pascal Génot

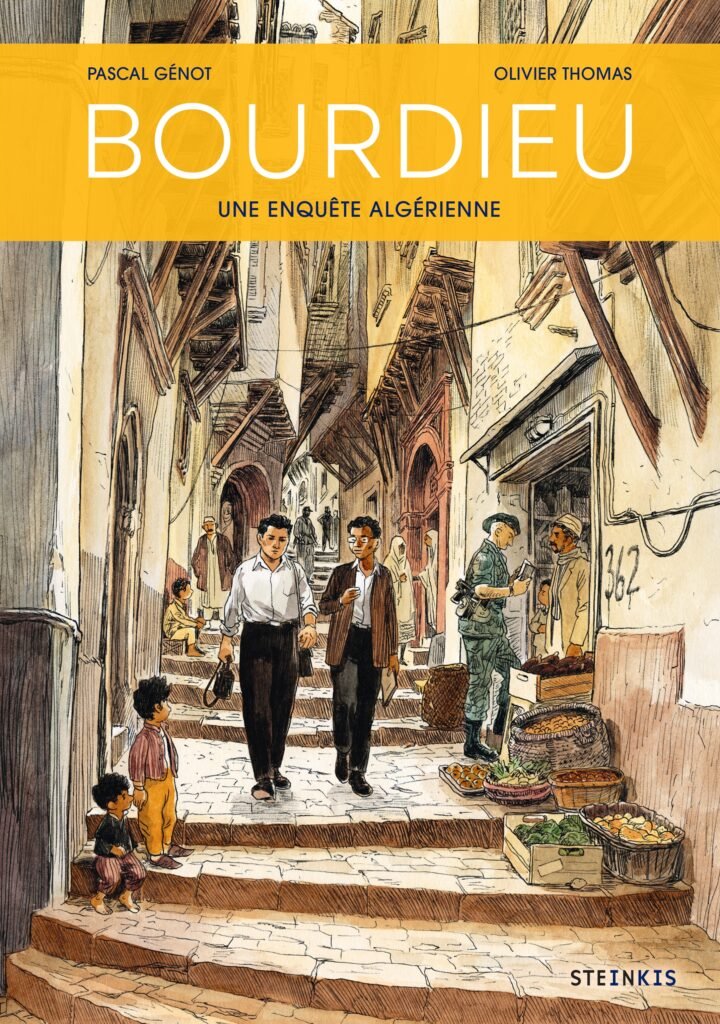

Bourdieu. Une enquête algérienne by Pascal Génot and Olivier Thomas (2023) is a graphic novel about Pierre Bourdieu’s Algeria. Pascal Génot, a screenwriter who holds a PhD in information and communication sciences, discusses the creation of this book.

It All Started with an Image

Starting in 2011, I had the opportunity to teach screenwriting at the International Comic Strip Festival in Algiers. Around the same time, after working on two fiction graphic novels (2005-2008; 2014) with Olivier Thomas, an illustrator, and Bruno Pradelle, a colorist and screen–writer, I wanted to move toward documentary work. The idea of a graphic novel about Bourdieu’s experience in Algeria from 1956 to 1960, during the colonial war — first as a soldier, then as a sociologist — came to me from a photo published in the proceedings of a colloquium on the writer Mouloud Feraoun (2010). This photo, taken in Algiers in 1958-1959, shows Feraoun and Bourdieu. At the time, Bourdieu was teaching sociology in Algiers. He had just completed his military service and published Sociologie de l’Algérie (1958). This image made me realize the significance of Algeria in his career. I was mostly familiar with Bourdieu’s sociology of culture and knew little about his work based on his Algerian field research. I read his articles compiled by Tassadit Yacine in Esquisses algériennes (Bourdieu, 2008), Enrique Martin-Criado’s critical essay Les deux Algéries de Pierre Bourdieu (2008), and Images d’Algérie, the catalog of the exhibition of Bourdieu’s photos at the Institut du Monde Arabe (2003). There was a fascinating subject here for a documentary graphic novel. Olivier Thomas, who viewed Bourdieu as a strong and endearing figure, a committed intellectual from a rural and modest background, was also interested in the project.

Between Reportage and Historical Reenactment

I had in mind the work of Joe Sacco, a pioneer of reportage graphic novels. Footnotes in Gaza: A Graphic Novel (2009) served as my model. In this book, where he attempts to reconstruct a massacre committed in Gaza in 1956, Sacco incorporates elements of docu–drama: a reportage on the site of the “story,” interviews, archives, and the reenactment of the event. In film, reportage and reenactment do not follow the same process. “Documentary” and “fiction” are semiotically “framed” separately. However, in a graphic novel, reportage and historical reenactment stem from a single process. Sacco does not distinguish graphically between reportage and reenactment, suggesting an equivalence in their relationship to reality. Both are “false” but aim to approach the same truth.

For Bourdieu. Une enquête algérienne, the goal was to be precise about what science allows us to say about Algerian society, the Algerian War, etc., while also engaging with the relationship between the graphic novel and reality. Like Sacco, I wanted to combine reportage and historical reenactment. For the reenactment scenes, the fictional techniques are clear, particularly in the alternation between a neutral narrative point of view and a focus on Bourdieu’s character. The reportage scenes, where I also appear as a character, are, of course, an artifice. But the semiotic framing “indicates” that what is narrated happened as it is told. The presence of the author-narrator as an investigator character places this part of the narrative within the framework of autobiography. Should I remain faithful to this framework? Or diverge from it?

From Documentary Investigation to Finding a Publisher

In 2015, I conducted an investigation in Algeria. I wasn’t looking for new facts about Bourdieu’s experiences — I relied on Amín Pérez’s thesis (2022). Instead, I was searching for documentary material: interviews with sociologists and witnesses, and photos of places where Bourdieu conducted research with Abdelmalek Sayad. I kept a journal because the investigation would form a thread for the script. I carried out this work with the help of a friend, Saadi Chikhi, who was my fixer and is represented as a character in the graphicnovel. A grant from the Institut Français covered half of this stay, and I funded the rest.

At the same time, I read Bourdieu’s and Sayad’s works on Algeria, books on the Algerian War, and articles, especially those by the sociologists I interviewed (Saïd Belguidoum, Kamel Chachoua,

Nadji Safir, Rachid Sidi Boumedine, Tassadit Yacine…). A central theme emerged: precarity. For Bourdieu, the precarity imposed on Algeria by colonialism echoed the precarity imposed later by neoliberalism. This theme gradually asserted itself in the script.

In September 2015, I was hosted in residence by the Agence algérienne pour le rayonnement culturel. I wrote a synopsis and sequences that Olivier Thomas illustrated for the proposal to publishers. We first received a favorable response from a well-known publisher but were asked to remove the reportage element. It was Steinkis Editions that accepted the project as conceived. We also received a rejection from a major publishing group, who argued that there was “no market space” for this book. That turned out to be false. Bourdieu. Une enquête algérienne has already been reprinted four times, exceeding 10,000

copies. It is a commercial success. Publishers underestimated the fact that in France, there is a graphic novel readership, particularly among secondary and higher education teachers, who are also “left-wing” and for whom Bourdieu matters.

Writing and Drawing

The writing and drawing took five years because the economics of creating this book didn’t allow us to make a living from it. We worked on it between other projects, during holidays… Even without that, the process would have been long, with many rewrites. It was essential that the content be both rich and accurate, and also accessible to a readership unfamiliar with the Algerian War, sociology, etc. The book is dense but relatively short considering the subjects covered. The result seems successful: I’ve heard that some teachers recommend the book to students. However, I don’t believe this graphic novel serves as an introduction to Bourdieu. I think it is less intimidating to approach “Bourdieu” when you see him evolve as a character in a graphic novel. For the script, in addition to alternating between reportage and biopic, I played with correspondences within the narrative. Some sequences respond to each other formally, like the one where Bourdieu takes photos in Algiers and the one where I do the same today. Other correspondences are thematic: for instance, the theme of borders recurs regularly. The link between the narrative and reality is clarified by a dialogue where I explain that the narration of the investigation anonymizes people as in

ethnography, and that I create fictional characters to represent ideal types. The reportage scenes are ultimately auto–fictional. The goal was to present a narrative while explaining the conditions that made this narrative possible and to suggest a critical reflection on the very status of this narrative. This ties into the importance of reflexivity for Bourdieu. Olivier Thomas’s drawing also found a balance with reality. It’s a “realistic” style, but in black and white with a “loose” line to speed up the process and avoid overloading the image with too many details. Olivier paid particular attention to the backgrounds to ensure they conveyed a “living” image.

A Reception Focused on Content

The reception of the book, at least in the press and through discussions with readers, made me realize that the subject of “Bourdieu” and the “documentary” framework limited interpretation. The possibility of reading this graphic novel on multiple levels does not seem to align with the public’s expectations. Perhaps because documentary graphic novels are often viewed primarily as vehicles of information rather than artistic expressions. At a time when the social sciences are exploring graphic novels as “alternative writing,” I fear that this approach may reach an impasse.1 If the goal is to disseminate knowledge to the widest audience, a successful graphic novel is still less effective than a video podcast. However, as a space for experimenting with representations of the world, graphic novels and social sciences can engage in dialogue. But this requires

both artistic and scientific rigor. Therefore, it demands a creative economy that matches the stakes. Like science, graphic novels require time.

References

- Alam, T. and Bué, N. (2023) “Un tournant ethno-graphique ? Ce que fait la BD aux sciences sociales et vice-versa”, communication at the “Écritures alternatives en sciences humaines et sociales” meeting. Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

- Bourdieu, P. (1958) Sociologie de l’Algérie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Bourdieu, P. (2003) Images d’Algérie. Une affinité élective. Arles/Graz: Actes Sud/Camera Austria.

- Bourdieu, P. (2008), Esquisses algériennes. Paris: Seuil.

- Génot, P., Pradelle, B. and Olivier, T. (2005-2008) Sans pitié. 3 volumes. Paris: Emmanuel Proust Éditions.

- Génot, P., Pradelle, B. and Olivier, T. (2014) Le Printemps des quais. Paris: Delcourt-Soleil Éditions.

- Génot, P. and Olivier, T. (2023) Bourdieu. Une enquête algérienne. Paris: Steinkis.

- (2010) Hommage à Feraoun. Proceedings of the colloquium held at the Amazigh Film Festival. Tizi-Ouzou.

- Martin-Criado, E. (2008) Les deux Algéries de Pierre Bourdieu. Vulaines-sur-Seine: Croquant.

- Pérez, A. (2022) Combattre en sociologues. Pierre Bourdieu et Abdelmalek Sayad dans une guerre de libération (Algérie 1958-1964). Marseille: Agone.

- Sacco, J. (2009) Footnotes in Gaza. New York: Metropolitan Books.