Fernanda Beigel, Denis Baranger and Alicia Gutiérrez

On November 11, 2024, the Practical Sense Newsletter was presented as a special event organized by the Research Center for the Circulation of Knowledge (CECIC) within the Workshop “Convergences between Bibliometrics and Prosopography: coverage studies, knowledge circulation, and academic asymmetries.” The webinar featured the participation of Johan Heilbron, Julien Larregue, Matthias Fringant, Carolina Pulici, Jéssica Ronconi, Alicia B. Gutiérrez, and Fernanda Beigel. This event also served as the opportunity to present the new Bourdieu Space: Argentina (EBA being its Spanish acronym), a recently created network to disseminate and engage in dialogue with Bourdieusian scientific research in the country.

In Argentina, the intellectual field has always been keenly aware of European developments, and particularly those from France: first, with the reception of the works of Sartre and Lévi-Strauss, followed by Althusser, Barthes, Lacan, Foucault, and Bourdieu. In fact, it was in Buenos Aires that El oficio del sociólogo was translated into Spanish for the first time in the world in 1976. Nearly a decade earlier, in 1967 Spanish translations of the famous issue of Les Temps Modernes containing Bourdieu’s article “Literary Field and Creative Project” (from Mexico’s publisher Siglo XXI) and of Los estudiantes y la cultura (from Spain’s publisher Labor) circulated in Argentina.

This dynamic reception was stunted in 1976 when a military dictatorship dismantled the social science departments in public universities and Sociology programs were closed throughout the country. Thousands of researchers and professors were imprisoned, or even disappeared, and the Argentinian intellectual field withered to its seeming death. It was not until the advent of democracy in the country and the reinstatement of the social sciences, beginning in 1983, that a national tradition of scientific research nourished by Bourdieu’s ideas began to unfold throughout Argentina. As in many other countries, Bourdieu has become the most cited author in both sociology and anthropology. It was only natural, then, for a group of researchers united by a common interest in putting Bourdieu’s categories and concepts to productive use to create a shared network; not as a site of reverence, but rather as a sort of laboratory that does not exclude the incorporation of ideas from other traditions.

With the creation of the Bourdieu Space in Argentina, whose very name indicates a limited degree of institutionalization, we aim to create an instrument capable of achieving a broader circulation of all information and developments related to work that draws from the Bourdieusian tradition – considered in its broadest sense – both in Argentina, and elsewhere. While a very rich set of research projects have been developed outside of Buenos Aires, the capital city has always distributed its symbolic and material resources in a manner that confers more visibility to those working in the metropolitan area. Accordingly, one of the Bourdieu Space’s main objectives is to integrate researchers that reside in the provinces, and in so doing avoid the predominating centralism in the Argentinian intellectual field. It is still possible to join the network, and thus far the EBA has 30 members from 10 different universities in the country.

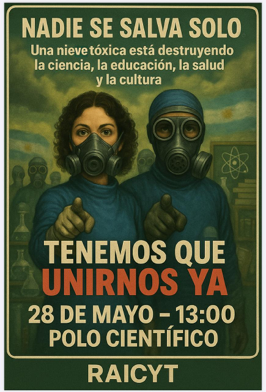

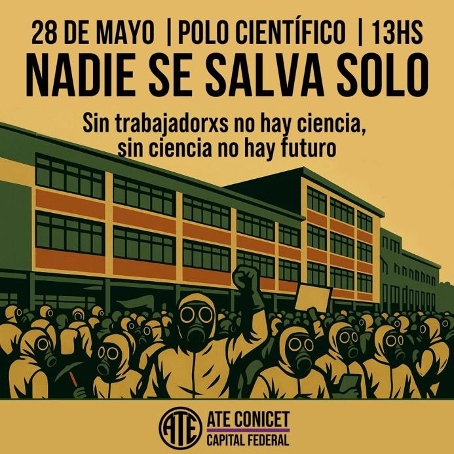

It is interesting to question why this initiative did not emerge earlier in a country where Bourdieu has been so widely read and cited. Moreover, that the Bourdieu Space came to fruition during a particularly critical moment for the scientific field and public universities in Argentina controlled by a self-proclaimed “anarchocapitalist” govern-ment that is implementing fast social changes that will increase inequality and is drastically defunding scientific research is significant. Perhaps, it is simply because we must stand together to resist this new, ultraconservative doxa coming from a government that is openly anti-rights and anti-science conducting what has been called a “scienticide.” And to remind ourselves that sociology, too, has its fair share of ammunition for combat.

Among the different actions and campaigns, on May 28, the researchers manifested in the streets with gasmasks, invoking a recent NETFLIX series produced in Argentina called the “Eternauta.” This emblematic comic strip, written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Francisco Solano López was published between 1957-1959. It tells the fictional story of a deadly snowfall that kills all the people in the streets and a few survivors must fight against an alien invasion. While struggling against the cruelty of the monsters that attack the humans, the main character – Juan Salvo – says “nobody is saved alone.” Struggling against the governmental attack over science, Argentina’s research community keeps working and resisting.